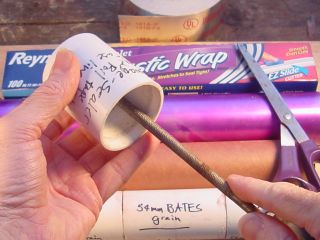

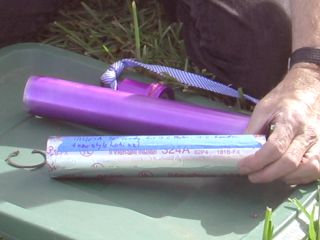

When I go to fly nowdays, it is usually with a 54mm motor.

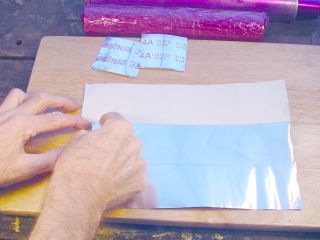

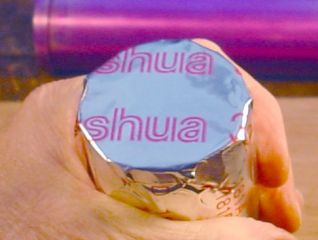

Here the techniques used for sealing up 38mm motors are adapted to the Loki-style 54mm propellant load to create a sealed package that is impervious to moisture, and thus can store sugar propellant loads indefinately.